possession

2022

Self-portrait.

“possession” statement

– I want to place things that belong to no one on the table.

Mari Katayama

Originally, it was objects who were the protagonists of my art. For them, I used my body as a mannequin, dressed up my room, and took my photographs. The images were labelled as self portraits, and I as a self-portrait artist, because I am in the pictures, too. When I began to work as an artist, Azumaya Takashi gave me a piece of advice: “Never confuse your work for yourself.” The work is not me. The work is not mine. The work makes me an artist. This is

what I have believed all along, and what has allowed me to continue my work. When I started working as an artist, I was often told things like, “Make your unusual body your subject and you’ll get attention” or “You’re a young woman, you’re disabled – the critics will love you” or “Our exhibition is about diversity, and we would like to include you as a disabled artist.” Because of such lines, when I was younger I tried my best to seem like a nondisabled person in my life and in my work. Sometimes I also disguised my age or wore suite made for men. “What is captured in the photographs is a mannequin.” In 2014, I took part in an artist residency, and I relocated to Gunma Prefecture to better focus on my artistic work. Around that year I began to point my camera no longer at objects but at my own body. For the artist residency and for my career as an artist, I had nothing to rely on but my body… In the end, working and living as an artist also means making a living as a part of society. Within this society, I am given the label “disabled.” I can’t hide from this fact, and I can’t pretend otherwise.

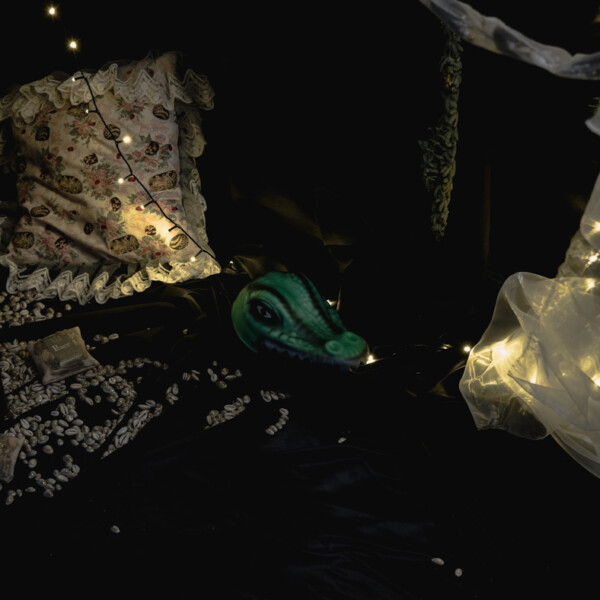

My series possession revolves around objects used in the three series shadow puppet, beast, and Thus I Exist, all created during my time in Gunma. In shadow puppet I faced my body directly, the way it looks, the way it works: “My arm is useful and diligent. Sometimes it functions as a leg, too.” For the series beast, on the other hand, I covered my body with pieces of lace, like scales of a fish, so that the contours of my body became hidden, as if trying to erase its shape altogether.

The series Thus I Exist was inspired by the story of Ukemochi, a Shinto goddess from the Nihon Shoki, one of the oldest books in Japanese history. Ukemochi kindly treated Tsukuyomi-no-Mikoto (god of the moon and brother of sun goddess Amaterasu) to a delicious meal made from her own excretions. Disgusted, Tsukuyomi killed her in a fit of rage. From Ukemochi’s corpse grew the five grains, the horses, the cattle and the silkworms that made life a pleasure for people on earth. How great for them. I learned about this story when I was 19 and studied art and aesthetics history. Hearing the story during class, my blood froze in my veins and I felt a strange vacuousness and anger towards some large injustice, something that can’t be changed by individuals. Why did she have to be killed in a fit of rage, why did her body have to be given to the humans? It was also frustrating not to find the right works to

express these feelings.

The doll in Thus I Exist consists of two sides; one shows the shells, hairs and beads with which it is filled, the other side is printed with photographs of my body. I myself don’t know which is front and which is back. They both have a spine and buttocks. Although I had aimed to create it at a like-like 140 cm, the finished doll measured 210 cm. When I noticed this I realized that I know myself much less than I had thought. But then again I wasn’t interested in understanding myself either.

I always took great care of these objects and was against selling them precisely because I felt that they are not mine. But as my exhibitions grew in scale and I became busier, I had to acknowledge that I won’t be able to care for them if I kept them with me any longer. I wanted them to be somewhere where they would be treated well. In the end, I decided to give all the objects I made during my early period, when I still pretended to be nondisabled, to a museum.

Every time I exhibited these objects, I stitched them with thread to keep them in place or to attach new decorations. I told the museum, “If they become damaged during an exhibition or deteriorate over time, please just repair them as necessary. Don’t try to keep them in their original state.” I also requested that whenever an exhibition takes place, the objects should be propped up on tables previously used by people in the region. I live and create in the current age, and so the art I make is contemporary. What is important in contemporary art is a sense of sharing an era. It is the life here and now that is important, and nothing embodies life here and now as much as a table. Each time a new table is found for an exhibition venue, the installation will be reconfigured accordingly.

To me, it feels extremely natural that an artwork should change in form and presentation just like my own body grows and ages as time goes on. Artworks will continue changing even after the people involved in creating or collecting them are gone. I was relieved when I realized this. Things do not belong to anyone after all. They are free; no one can possess them, and no one can make them their own. They do not have to be judged by anyone. No one else decides whether they live or die, no one else chooses their fate.

I want to place things that belong to no one on the table.

“possession” ステートメント

誰のものにもならないものをテーブルの上に乗せたい。

片山真理

初期作品のオブジェが美術館へ収蔵されることが決まり、収蔵先の美術館とコンディションやメンテナンス、展示方法などの打ち合わせをしている。

「possession」は、この中には含まれずスタジオに残った「Thus I Exist – doll」、「shadow puppet – doll」、「beast」のオブジェを中心に撮影したセルフポートレートだ。どれも作家活動に専念するため群馬県へ拠点を移してから制作したもので、それぞれを主体とした写真作品も発表している。それらを作るまで、主役はオブジェであり、それを説明するためのマネキンとして自身の身体を利用し、写真を撮ってきた。その写真に私自身が写っていたため、作品は”セルフポートレート”と呼ばれ、私は「セルフポートレーター」と呼ばれるようになった。制作を始めた頃、師匠の東谷隆司氏に「作品と自分自身を同一視してはいけない」と忠告を受けたことがあった。その言葉のおかげで、私は制作を続けられている。作品は私じゃない。作品は私のものでもない。作品が私を作家にさせている。ずっとそれを信じている。

そんな作品に対し(今思うと本当に馬鹿げた言葉だが)、「特異な身体を被写体にすれば注目されるだろう」、「君の作品が評価されるのは君自身が障害者で若い女の子だからだよ」という言葉を投げかけられる度、当時20代前半だった私は、作品と私は別物だけど、私自身が「健常者のような」生活や制作、作品ができるよう努力していた。女性的ではないように振る舞ったり、年齢を偽ることもあった。

しかしアーティストレジデンスの滞在中に制作した「you’re mine」や、滞在先の街で撮影したセルフポートレート作品「25 days in tatsumachi studio」をきっかけに、カメラを向ける対象がオブジェから身体へ変わっていった。身一つで挑んだアーティストインレジデンスも、作家活動に専念すること……つまり経済活動をしていくことも社会と密接に関係していたからだ。この社会では、私は「障害者」と位置付けられていて、もう障害者であることを隠すことも、健常者のふりをすることもできなくなってしまったのだ。

そんな時、制作した作品が「Thus I Exist – doll」、「shadow puppet – doll」、「beast」だった。「shadow puppet」シリーズでは「私の働き者で便利な手は時には足にもなる」と、からだの「かたち」や「しごと」に向き合い、シルエットを強調するようなモノクロのセルフポートレートを撮影した。対して、同時期に制作した「beast」はからだのかたちを打ち消すように、全身をすっぽりと覆い、鱗のように覆われたレースの一片が、はっきりと見えないからだに沿ってその輪郭をぼやかしている。

「Thus I Exist – doll」の着想を得たのは「日本書紀」に出てくる保食神(うけもちのかみ)のストーリーである。ざっくり説明すると、天照大神に命令され月夜見尊が保食神へ会いにきた。保食神は美味しい料理で月夜見をもてなす。なんでこんなに美味しいんだろうと調理場を覗くと、美味しい料理は保食神の排泄物であった。それを汚いと怒った月夜見尊は保食神を殺してしまった。殺された保食神の体から、五穀、牛馬、蚕が生まれ人間の生活を豊かにしたのだった。めでたしめでたし。

この話を知ったのは、文学部で美学美術史を学んでいた19歳の時で、授業でこの話を聞いた時は血の気がひいた。とてつもなく大きくて、人一人の力では変えられないなにかへの虚しさや憤りのうようなものを感じた。なんで怒られて殺されて人々に与えられなきゃならないの。いや、しかし、これは日本書紀。それは突っ込むところじゃないか。けれども、このもやもやを具体的にことばにできないことがとても悔しかった。

「Thus I Exist – doll」は貝や髪の毛、ビーズなどが入っている側面と、身体の写真をプリントした布を縫い合わせた側面とで、どちらが裏なのか表なのかわからない。そしてどちらの面にも背中とお尻がついている。制作時、140cmの等身大になるよう計測し制作したはずなのに、仕上がったものは210cmになってしまった。それを見て、「自分が思うより、自分のことってわからないんだな。だからいつも服が合わないのかな」と思った。かといって自分自身を把握したいとも思えなかった。

作品は私のものではないからこそ大切に扱ってきた。けれども、展示の規模や活動が大きくなるほど、これ以上私が保管していたら大切にできなくなると感じた。だから大切にしてくれるところに持ってもらおう。そうして決まった収蔵だった。

これまでオブジェたちは展示の際に崩れや盗難防止のため、糸で縫って固定していた。搬出時、固定の糸を解きながらほつれを縫い直す。時にはビーズや装飾を付け足したり、コラージュ作品に至っては上からテープやシールを貼っていた。「もし展示で破損したり、経年劣化したりしたら、そのままの状態でキープするのではなく、メンテナンスや補修をしてください」と収蔵先に伝えた。

また、展示方法については「オブジェを展示する地域で使われていたテーブルを展示台にしてほしい」とリクエストをした。現代に生きて作っているから、私は現代アートをしていると自覚している。そしてその現代アートにとって大切なことは同時代性だ。だから「今ここ」の生活が大切で、展示される地域で使われているテーブルは「今ここ」の生活そのものだ。そして「展示される場所で展示台を見つけてもらう」度に、オブジェのインスタレーションは再構成されていく。

そうやって作品の姿形や展示が変化していくことは、老いや成長のような時間軸を内包する身体と同じで私にとって至極自然なことだった。たとえこの作品や収蔵に関わった私たちがいなくなってもきっとずっと変化は続いていく。それを思った時、「あぁ、『誰のものでもない』な」とホッとした。誰にも所有されることはない(たとえ望んだとしても)、誰のものにもならない自由を持っている。だから他人にジャッジされる必要なんてない。他人に生死を選択されたり、与えられたりするものじゃない。誰のものにもならないものをテーブルの上に乗せたい。

CATEGORIES